Understanding Habit Formation in Healthy Eating and Activity

An educational exploration of how habits form, the patterns that shape our daily choices, and the behavioural science behind sustained routines.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

The Habit Loop Explained

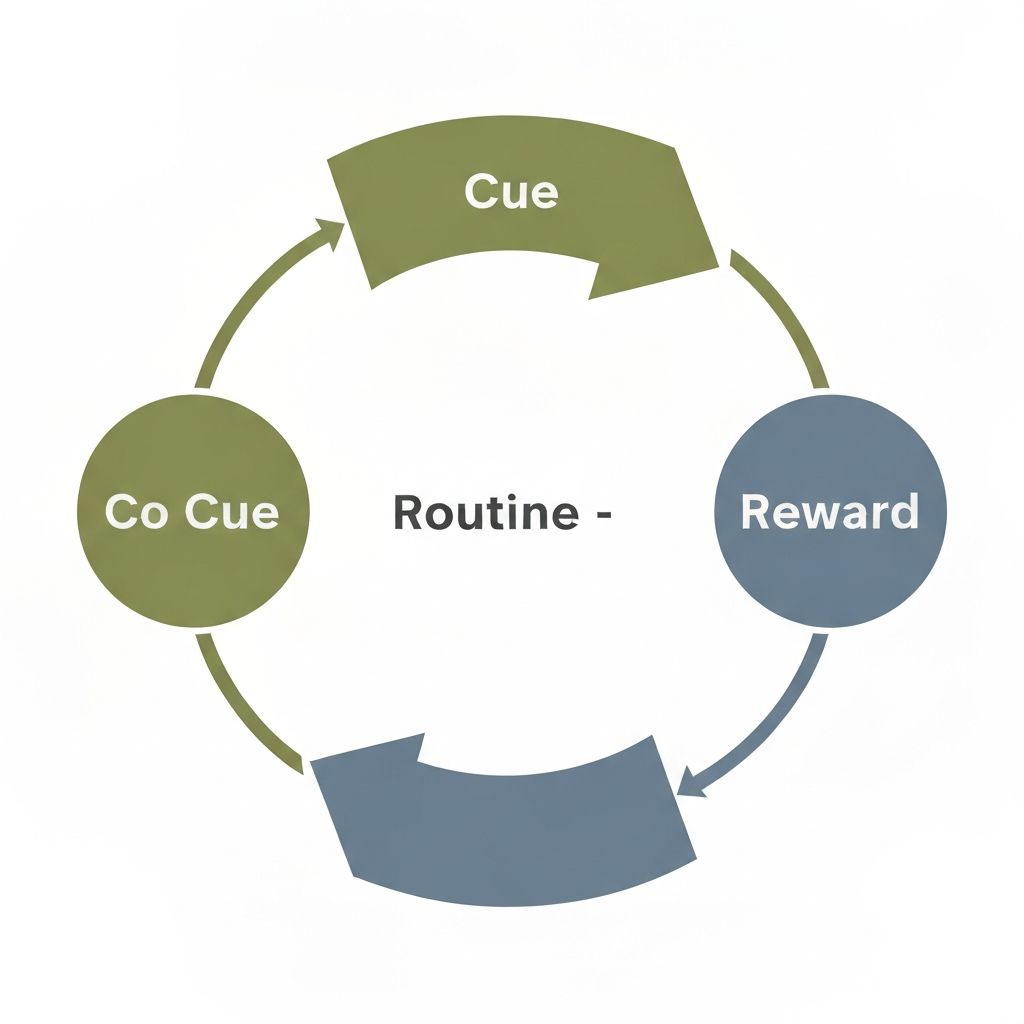

At the core of habit formation lies a simple model: the habit loop. This framework, grounded in behavioural science, consists of three interconnected elements that together create the foundation for repeated behaviours.

Cue: The trigger that initiates a behaviour. This can be a time of day, location, emotional state, or preceding action.

Routine: The behaviour itself — the action performed in response to the cue.

Reward: The positive outcome or feeling that reinforces the behaviour, making it more likely to repeat.

Understanding this cycle helps explain why certain actions become automatic and how environmental and contextual factors support repetition.

The Role of Small, Consistent Changes

Significant change rarely happens overnight. Instead, lasting shifts in behaviour often result from small, incremental adjustments compounded over time. This principle, often referred to as the concept of marginal gains, demonstrates how modest improvements sustained consistently can accumulate into meaningful patterns.

When changes are small and manageable, they fit more naturally into existing routines, reducing the cognitive load required to maintain them. This consistency matters more than intensity: a modest adjustment practiced daily has greater cumulative impact than an ambitious change attempted sporadically.

Research on behaviour change shows that individuals are more successful when they focus on building one small habit before adding another, allowing new routines to stabilise before further expansion.

Environmental Design Principles

Our surroundings exert a profound influence on the choices we make daily. Environmental design — intentionally structuring physical and social spaces — plays a critical role in supporting repeated behaviours.

When items associated with desired routines are visible and accessible, they serve as natural cues. Conversely, removing friction from desired activities and adding friction to undesired ones shapes decision-making in subtle ways.

This concept extends beyond physical spaces to include digital environments, social contexts, and the temporal structure of daily life. By understanding how environment influences behaviour, individuals can design settings that make desired routines easier to maintain.

Repetition and Context Stability

Habits strengthen through repetition in stable contexts. The brain learns through consistency: when the same cue appears in the same setting, the associated routine becomes increasingly automatic.

Context stability — repeating behaviours in consistent locations and times — reinforces neural pathways and reduces the mental effort required to execute routines. This is why changing environments (travel, relocation, schedule changes) can temporarily disrupt established patterns.

The relationship between repetition and context explains why successful habit maintenance often depends on creating routine in daily life. Variability in when and where activities occur requires greater conscious effort to sustain.

Self-Monitoring Concepts

Self-monitoring refers to the practice of observing and tracking one's own behaviour. This awareness can influence behaviour by creating a feedback loop: noticing patterns provides information that informs future decisions.

However, self-monitoring exists on a spectrum. Simple awareness — occasionally reflecting on routines — differs markedly from intensive tracking. Research suggests that moderate self-awareness supports behaviour consistency, while excessive tracking can sometimes create unproductive focus or pressure.

Effective self-monitoring emphasises pattern recognition and reflection rather than measurement. Understanding the relationship between behaviours, contexts, and outcomes develops insight without requiring elaborate tracking systems.

Stages of Behaviour Change

Behavioural science describes several recognisable stages people move through when changing habits:

- Pre-Contemplation: Not yet considering change; may lack awareness of patterns.

- Contemplation: Aware of patterns and considering change, but not yet committed.

- Preparation: Ready to change; beginning to make adjustments and gather information.

- Action: Actively implementing new routines; requires conscious effort and intention.

- Maintenance: Sustaining new patterns; requires ongoing attention but demands less conscious effort than action stage.

Understanding which stage applies to a particular behaviour helps set realistic expectations. Different stages require different approaches: information is most useful during contemplation and preparation, while support and environmental design matter most during action and maintenance.

Identity-Based versus Outcome-Based Approaches

Two distinct conceptual frameworks shape how people approach habit formation:

Outcome-Based Approach: Focuses on achieving a specific external result. "I want to feel more energised" or "I want to move more" centres on desired outcomes.

Identity-Based Approach: Focuses on the type of person one becomes. "I am someone who enjoys walking" or "I make nourishing food choices" builds habits around identity rather than external goals.

Research suggests identity-based approaches create more resilient habits because they address the question "Who am I?" rather than "What do I want?" Identity-aligned behaviours feel inherently motivating rather than externally driven, supporting long-term consistency even when external rewards or outcomes fluctuate.

Social and Emotional Influences

Human behaviour exists within social and emotional contexts. The people around us, our emotional states, and social norms significantly influence daily choices and habit formation.

Social support — both explicit encouragement and simply having others engaged in similar patterns — shapes behaviour through various mechanisms: modeling (learning by observation), accountability, and shared reward systems.

Emotions also play a critical role. Stress, boredom, loneliness, or contentment influence which routines feel appealing. Understanding the emotional drivers behind behaviours provides insight into why certain patterns emerge and how environments that support emotional well-being may support habit consistency.

Common Obstacles to Consistency

Decision Fatigue: The mental effort required to make decisions depletes over a day. When routines aren't habitual, they demand conscious choice, increasing susceptibility to fatigue-driven deviations.

Motivation Variability: Motivation naturally fluctuates. Days of lower motivation reveal whether routines are truly habitual (requiring minimal willpower) or still dependent on conscious effort.

Environmental Changes: Travel, schedule disruption, or relocation disrupts established context-behaviour associations, temporarily destabilising routines.

Competing Priorities: When multiple demands exist simultaneously, established patterns may be displaced by urgent tasks or unexpected events.

Feedback Delays: Some behaviours lack immediate, clear rewards. Without proximate feedback, motivation to sustain routines diminishes.

Recognising these obstacles as normal aspects of behaviour change, rather than personal failures, supports more constructive responses when patterns are disrupted.

Explore Deeper Insights

Our detailed articles explore specific aspects of habit formation, behaviour change science, and the factors that influence daily patterns.

How Cues and Rewards Shape Behaviour

Discover how environmental and internal cues trigger routines, and how rewards reinforce repeated patterns.

Learn moreSmall, Sustainable Adjustments

Explore the science of incremental change and how consistent small steps create meaningful patterns.

Learn moreEnvironmental Design Principles

Understand how physical and social environments shape behaviour and support habit formation.

Learn moreStages of Behaviour Change

Learn the recognised stages people move through and what supports progress at each phase.

Learn moreOvercoming Disruptions

Explore strategies for maintaining consistency when routines are interrupted.

Learn moreIndividual Differences

Understand why habit formation timelines vary and how individual factors influence patterns.

Learn moreFrequently Asked Questions

Habit formation timelines vary considerably based on individual factors, the complexity of the behaviour, frequency of repetition, and consistency of context. Research suggests ranges from weeks to several months, but variability is substantial. Consistency and context stability matter more than time elapsed.

Routines are intentional sequences of actions; habits are behaviours that require minimal conscious effort. A habit is an automatised routine. Both involve repetition, but habits operate with reduced cognitive demand, occurring more automatically in response to contextual cues.

Environment serves as the context in which cues appear and behaviours occur. Physical spaces, social settings, and temporal structures all influence which cues are present, which actions feel accessible, and which outcomes feel rewarding. Deliberately designing environments can support habit formation by making desired behaviours easier and more natural.

Habits can be modified or replaced rather than simply "broken." Because habits are cue-routine-reward associations, changing one element of the cycle can disrupt the pattern. Substituting a new routine in response to the same cue, or removing the cue from one's environment, are evidence-supported approaches.

Motivation supports initial behaviour change and the early stages of habit development. However, true habits require less motivation because they become automatic. Well-designed habits reduce dependence on motivation by making behaviours easier through environmental support and repetition in stable contexts.

Emotions serve as both cues for behaviour and as rewards or punishments. Stress, boredom, joy, or frustration can trigger certain habits. The emotional satisfaction (or lack thereof) experienced after a routine influences whether the behaviour is repeated. Understanding emotional drivers provides insight into habit patterns.

Identity-based habit formation focuses on adopting beliefs about the type of person you are. Rather than "I want to achieve X outcome," the approach emphasises "I am the type of person who does Y." This identity alignment supports habit persistence because behaviours feel intrinsically motivated rather than externally driven.

Social support influences habit formation through multiple mechanisms: modeling (observing others performing desired behaviours), accountability (knowing others are aware of our intentions), and shared rewards (experiencing positive outcomes alongside others). Social environments can either support or hinder habit development.

Disruption — such as travel, schedule changes, or illness — breaks the context-cue-routine association. When the familiar environment changes, habits may not be automatically triggered. Recovery often involves re-establishing the routine in the familiar context or deliberately re-creating environmental cues in new settings.

Yes. Understanding habit mechanisms — cue-routine-reward cycles, the role of context, the importance of consistency, and the stages of behaviour change — provides a framework for approaching behaviour change more strategically. This knowledge supports more realistic expectations and more effective strategies.

Continue Exploring Behavioural Patterns

Discover more detailed articles and insights about habit formation and behaviour change science.

View All Articles